Friday, February fourteenth, the UN says at least 22 people have been killed in a village in the Northwest region of Cameroon. Over half of those killed were children. No one has claimed responsibility for Friday’s incident but the opposition parties blame the killing on the government.

Why I don’t want to be Llbeled as ‘African-American’

- Get link

- Other Apps

One

afternoon in second grade on the bus home, my best friend Carly asked me why my

hair was so curly. I simply responded that it was because I was black. She

gently placed her hand on my shoulder in an almost compassionate manner and whispered,

“African-American.”

I

have heard the term “African-American” used interchangeably with “black” all my

life but have never been comfortable with it. Whenever I had to fill in a box

describing my race, ethnicity, or nationality, I would always check

“African-American,” but couldn’t help but wonder why the other kids in my

predominantly white school weren’t labeled by their ethnic roots. My peers

would proudly claim to be “half-German” and “a quarter Italian” or “16 percent

Irish.” They would brag about their family’s traditions: the foods they ate,

the holidays they celebrated, the languages their grandparents would teach

them. Yet none of them had to check a box that said “German-American” or

“Italian-American.” They were just white Americans.

I

was baffled by white kids’ ability to be in touch with their heritage without

having to label it, whereas I felt forced to identify as “African-American”

even though I couldn’t even tell you which of the 54 African countries my

ancestors are from. This is likely true for most black Americans whose

ancestors were slaves, as slaveowners historically made sure that their workers

lost ties to their homelands. The thousands of African ethnic groups — each

with its own language and customs — eventually merged to create a new culture.

This history has left me without any emotional ties to Africa. I know nothing

about the continent and feel 100 percent American, but am still forced to label

myself in relation to this foreign land.

For

years I not only felt disconnected from these roots but ashamed of them. As the

only black kid in a room full of white students, I learned that black people

once weren’t considered human in this nation and were forced to be completely

submissive to their white owners. I was ashamed to realize that my peers whose

families had lived in the South -— particularly Alabama, where my dad’s family

is from — could be the descendants of slaveowners who owned my family. In

middle school, I even wore hazel-colored contacts and rocked a long, wavy weave

and tried to tell people that I was biracial, even though everyone in town knew

my parents and could clearly see that they were both black.

One

day I had a talk with my mom about these feelings. She told me that instead of

feeling embarrassed about my family’s past, I should be proud. My ancestors may

have been enslaved, but only the strongest survived those torturous years. Of

the 10 million Africans that were brought through the Middle Passage, I was a

descendant of the toughest, healthiest, and most capable captives.

Perhaps

my mom exaggerated historical details to cheer up her 10-year-old, but from

that day forward, I learned to admire the traits that my strong forefathers

passed down to me. Sure, my incredibly oily skin causes more bumps on my face

than I would prefer, but this oil is the same that once made my late

grandmother, my mother, my sister, and me all look as though we could have been

born in the same generation. My skin doesn’t sag or wrinkle, and I’ve never had

a sunburn in my life. I’ll always find watching girls put on layers of

sunscreen in the summer, only to later complain about their peeling faces and

their pale complexions in the winter, entertaining. It never gets old to stick

my arm into the mix of girls comparing theirs to see whose tan lasted longest

into the cold months and proclaim that I have a “year-round tan.”

The

shame that I once felt about my race is now gone. Even though I have no record

of who my ancestors were or where they came from, I respect them for fighting

to survive long enough to pass on their traits to future generations, including

me. I label myself as American first, but I am still black — and damn proud of

it.

Popular posts from this blog

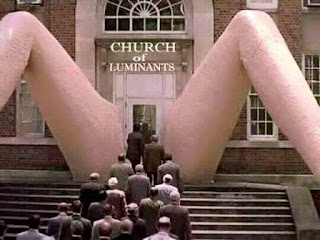

Entrance design of "Church Of Luminants" in USA

UN says at least 22 people including children killed in Cameroon's English-speaking region

Cameroonian scammer arrested in Montreal (canada

The Sûreté du Québec announced Wednesday the arrest of an alleged fraudster specialist of a scenario called "Black money scam", in which victims are invited to participate in the cleaning of soiled banknotes, then are robbed during the operation. Cyrille Ngogang, 49 years old, was caught red-handed in downtown Montreal Tuesday afternoon. He appeared in court this morning to be charged with fraud and breach of commitment. The man is not in his first trouble with the law: he was previously arrested by the SQ on 19 January for charges related to the same scheme, and had been able to resume its freedom under strict conditions pending his trial. There are several variants of the 'Black money' scenario, but all involve a so-called batch of cash that has been stained with a dye or colouring substance. Scammers ask their victim to provide money to clean the hoard.

Comments

Post a Comment